Metal meets reality.

I’ve seen teams spec a “server chassis” like it’s a tidy enterprise rack problem—until they try to jam it into a shallow cabinet beside a rectifier, pull air through dust and cable spaghetti, and then pretend MTTR won’t explode when every service action needs a full rack pull and two people.

And then they act surprised when the pilot dies—why?

Let’s be blunt: a telecom rackmount server case is not judged by your CAD render. It’s judged by whether a field tech can swap a fan at 2:10 a.m., whether it behaves on -48V DC without drama, and whether your enclosure choices reduce (or multiply) truck rolls.

I’m going to give you the hard truth version, with receipts, and a few opinions that will annoy the “just ship it” crowd.

The inconvenient market signal hiding in plain sight

Short sentence. Big numbers.

The reason chassis design for 5G edge sites suddenly gets political is that carrier infrastructure is being forced through replacement cycles and budget constraints at the same time. In May 2024, the Federal Communications Commission publicly flagged a “rip and replace” funding gap: $1.9B appropriated against ~$4.98B in reimbursable costs, plus prorated support at 39.5% for some applicants—i.e., cost pressure becomes policy, and procurement gets brutal.

So what happens next? Buyers become allergic to anything that looks “custom” but behaves “unproven.”

Now stack that with energy math. The U.S. Department of Energy points to U.S. data centers hitting 176 TWh in 2023 (4.4% of total U.S. electricity), and projecting 325–580 TWh by 2028 (6.7–12%).

Edge sites don’t have hyperscale cooling budgets. They get tight power envelopes and tighter patience.

And the edge-cloud market itself is still uneven. A Reuters report relaying ETNO numbers said Europe had four commercialised edge-cloud offers in 2023 versus 17 in Asia-Pacific and nine in North America; it also noted 59.1B euros of sector investment and only 10 of 114 networks being 5G standalone.

Translation: in a lot of regions, edge is still “selective,” which means your hardware has to win on operational friction, not hype.

What edge sites do to a rackmount server chassis

Three words: heat, dust, power.

A 5G edge server enclosure lives in micro-PoPs, cabinets, CO racks, shelters, “repurposed” rooms—places where airflow isn’t clean, rack depth is a negotiation, and the power plant speaks DC first.

Here’s what I’d treat as non-negotiable design inputs:

- Short-depth reality: 19-inch rack doesn’t mean “deep.” I see shallow cabinets that force 350–450 mm depth targets (sometimes less, once you count bend radius and rear cabling). If you design like 600–800 mm is free, you’re designing for returns.

- Front-service bias: Rear access is often blocked by power gear, fiber trays, or just… walls. If a tech needs to pull the whole chassis to replace a fan, you’re paying that cost forever.

- EMI/grounding discipline: Edge means radios nearby, noisy power conversion, and lots of “mystery” interference complaints. Mechanical bonding and gasketing become system reliability, not “nice-to-have.”

- Power input sanity: -48V DC rackmount server chassis isn’t a vibe; it’s how telco plants are built. You want clear DC entry, fusing, labeling, and protection against reverse polarity and transients.

And yes, the standards world agrees on the direction of travel. National Institute of Standards and Technology discusses 5G driving new requirements across storage/compute/network domains and explicitly ties 5G to enabling edge computing.

So: don’t treat “edge” like an afterthought. It becomes the constraint-set.

Design moves that separate “ships” from “sticks”

I’m opinionated here, because I’ve watched the same failure modes repeat.

1 Build for shallow racks without strangling airflow

Short-depth rackmount server chassis designs often fail because teams shorten the box but keep the same thermal assumptions. Bad move.

What works:

- Strict front-to-back airflow (no side leakage games).

- Ducting and blanking so air doesn’t take shortcuts.

- Fan strategy matched to impedance (dense filters + restrictive bezels need pressure, not just CFM).

If you want examples of how a manufacturer frames validation thinking, iStoneCase has a practical write-up on rackmount server case testing and validation that leans into failure modes and sign-off logic rather than pretty renders.

2 Treat -48V DC as first-class, not an adapter problem

I’m going to say the quiet part: many “-48V ready” builds are just AC-first designs wearing a DC costume.

A real -48V DC rackmount server chassis approach usually needs:

- DC input module space (and heat handling)

- Proper fusing and clear labeling

- Surge/transient considerations

- Cable management that assumes thicker conductors and different connector practices

If you want a grounded discussion around low-voltage environments from the same ecosystem, this internal piece on wallmount server chassis use cases in edge computing and low-voltage environments is surprisingly direct about DC realities and wiring discipline.

3 Assume service happens under stress

Telecom racks are service theaters. The audience is impatient.

Design for:

- Front-access hot-swap bays where practical (especially if storage is local)

- Captive screws (lost hardware is downtime)

- Clear I/O labeling (field swaps aren’t done by the engineer who wrote the spec)

- Rail compatibility and safe pull-out service positions

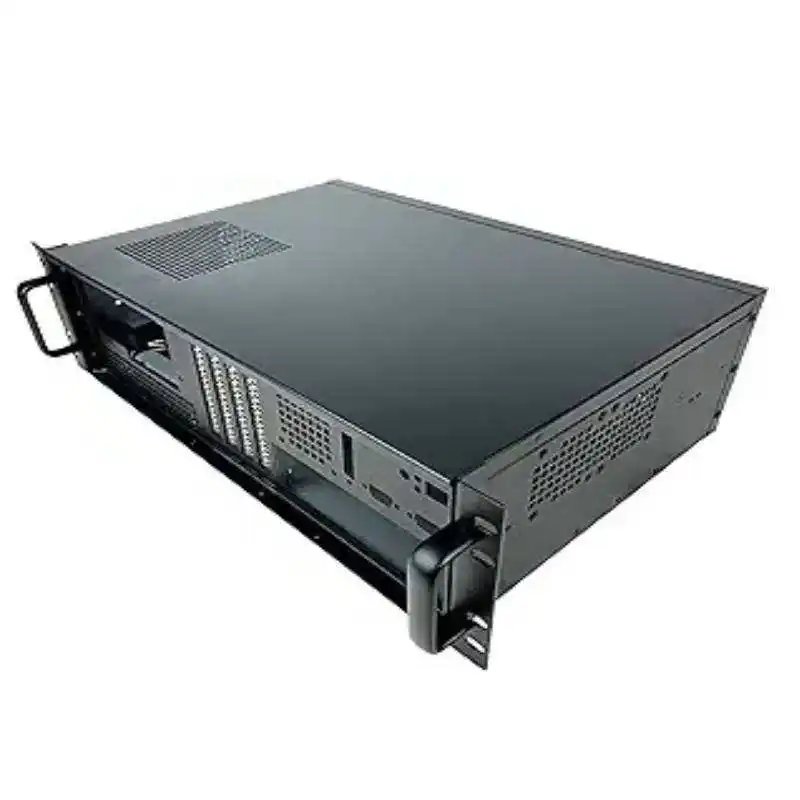

This is where “generic enterprise chassis” gets punished. You can browse typical form-factor baselines in a catalog like 1U rackmount case options and 2U rackmount case options to see the ecosystem of layouts buyers expect before they even entertain customization.

4 Be honest about what needs to be custom

Custom doesn’t scare buyers. Unbounded custom scares them.

A sane custom rackmount chassis scope is usually:

- depth + mounting + airflow path

- DC entry + grounding points

- front panel + I/O + security features

- vibration hardening + cable strain relief

The “OEM/ODM framing” matters here, because it tells buyers your changes have a process. See the internal primer on custom rackmount server chassis for how they pitch customization without turning it into chaos.

A quick comparison table buyers actually use

| Requirement (Telecom / 5G Edge) | What breaks in generic chassis | Design target that survives |

|---|---|---|

| Short-depth deployment | Rear cabling collision, airflow recirculation | 350–450 mm depth variants, front-to-back ducting |

| -48V DC power plant | AC-first PSUs, messy conversion blocks | Dedicated DC entry, fusing, labeling, protection |

| Field serviceability | Full rack-pull for fan/drive swaps | Front-service bays, captive fasteners, clear labeling |

| EMI/grounding discipline | Intermittent faults, radio noise complaints | Robust bonding, gasket strategy, tidy cable paths |

| Edge thermal reality | Dust loading + pressure drop kills cooling | Filter strategy + pressure-capable fans + blanking |

| Open RAN / MEC expansion | PCIe layout conflicts, weak card retention | Slot planning, retention brackets, strain relief |

The Open RAN / MEC angle most chassis teams miss

Open RAN / MEC edge server chassis builds tend to drift toward “more NICs, more acceleration, more heat”—and that’s where 1U fantasies go to die.

You can absolutely do 1U at the edge. But your thermals, acoustics, and service moves get tight fast, especially once you add accelerator cards, dense NVMe, or high-power NICs. I’m not anti-1U; I’m anti-magical-thinking.

So here’s my litmus test: if your “best” design requires pristine intake air and rear access to stay within spec, it’s not an edge design. It’s a lab design. Want to bet your SLA on that?

FAQs

What is a rackmount server case for telecom and 5G edge sites?

A rackmount server case for telecom and 5G edge sites is a 19-inch enclosure engineered for shallow-rack constraints, harsh airflow and dust conditions, and carrier operational practices—often including -48V DC power integration, front-service maintenance, EMI/grounding discipline, and mechanical durability aimed at minimizing truck rolls and downtime.

In practice, the enclosure is part of the network, not just a container—because field service and power/thermal quirks decide whether deployments scale.

What does “NEBS Level 3 compliant server chassis” mean in plain English?

A NEBS Level 3 compliant server chassis is an enclosure and system design intended to meet the strictest carrier-grade criteria for physical, electrical, and environmental robustness used in telecom facilities, typically including requirements aligned to Telcordia documents for safety, EMC, and resilience so equipment keeps operating under stress rather than failing gracefully.

Buyers use “Level 3” as a shorthand filter: it signals you designed for carrier acceptance, not hobby racks.

Why do telecom sites use -48V DC, and what does it change for chassis design?

-48V DC in telecom is a centralized power architecture where battery-backed DC plants feed equipment directly, reducing conversion steps and supporting reliability during grid events; for chassis design it forces proper DC entry, fusing, labeling, grounding, polarity protection, and thermal space for conversion or DC-DC modules instead of treating power as an afterthought.

If your enclosure forces ad-hoc conversion bricks and sloppy wiring, you’re manufacturing outages.

What is a short-depth rackmount server chassis and when do you need it?

A short-depth rackmount server chassis is a reduced-depth 19-inch enclosure (commonly targeting shallow cabinet realities) designed to fit racks where rear clearance, cable bend radius, or adjacent power/fiber hardware eliminates standard depth; you need it in edge cabinets, micro-PoPs, closets, and constrained telco bays where “full-depth” becomes physically impossible.

Short depth without airflow planning is a trap—make sure thermal design is part of the brief.

How do Open RAN and MEC change rackmount server chassis requirements?

Open RAN and MEC change rackmount server chassis requirements by increasing the density of high-speed NICs, timing and synchronization needs, accelerator cards, and edge-local storage, which raises power draw and heat while also amplifying serviceability demands; mechanically, it pushes you toward stronger card retention, cleaner front-to-back airflow, and fewer assumptions about rear access.

This is where “generic server chassis” starts losing bids—because integration pain becomes ongoing OPEX.

Conclusion

If you’re designing a rackmount server case for telecom and 5G edge sites and you want fewer surprises, start by bounding the constraints: rack depth, -48V DC, front-service rules, and your validation plan. Then spec the enclosure around that reality.

If you want a faster path to a manufacturable spec, look at the baseline catalog pages for 1U rackmount cases and 2U rackmount cases, then use a controlled customization approach like the one outlined in their custom rackmount server chassis guide.